Written by Jeff Hobbs

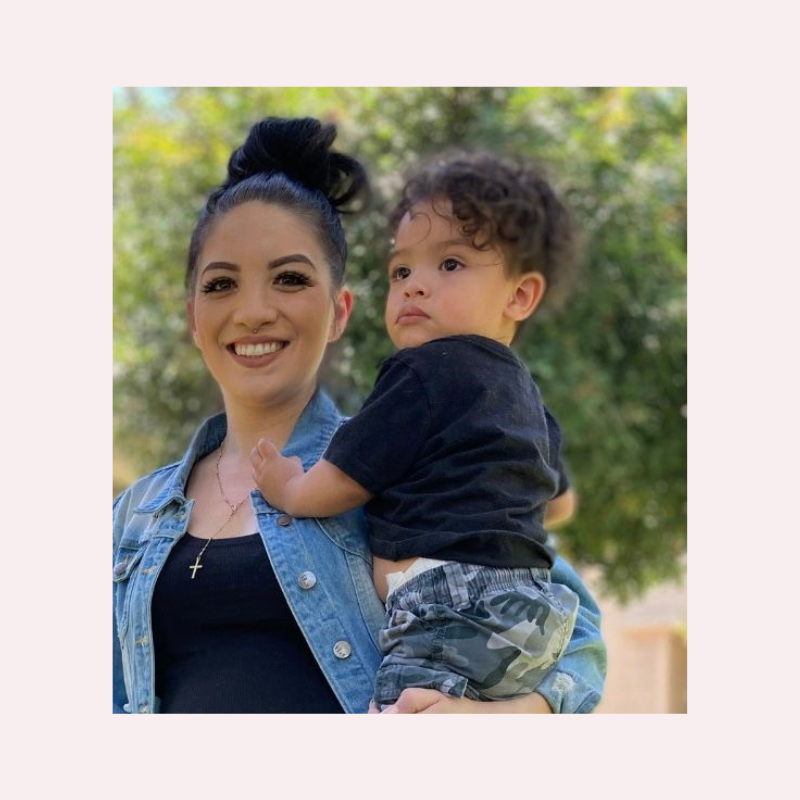

During the summer of 2018, Evelyn convinced her husband and five children to move from an impoverished, dangerous community in Southern California’s high desert region to a well-rated school district in Los Angeles.

She intended to save those children from the challenges that had defined the first thirty years of her own life.

These challenges encompassed generational poverty, gangs, abuse, under-resourced schools, and grueling work in the service sector. Evelyn’s story already was one of remarkable resilience.

Yet she wanted her children to have access to a higher-quality education than she’d had and to avoid entirely the costly dysfunctions of her youth.

So, Evelyn and her husband saved a few thousand dollars, conducted a few dozen hours of research on the school district online, and then gathered all their courage and resources to move to Los Angeles.

They believed at the time that determination and dignified intentions could trump all the city’s renowned disparities.

Over the next few months, her children loved their new school. They were inspired by their diligent classmates and invested teachers. They were thriving.

But every other aspect of her vision crumbled quickly. The average rent for a two-bedroom apartment was nearly one and a half times the minimum wage salary for someone working forty hours per week.

They were unable to find an apartment in the school district and had used up all their savings on motel rooms.

Her husband struggled to find work and began drinking, and this spiral resulted in an intense incident of domestic violence inflicted on her oldest son and herself. Evelyn and her kids left him.

Evelyn’s Dream of a New Life Turned Into Her Becoming a Homeless Mom

She was working as a server at Applebee’s but could not support her family alone. Less than three months into that school year, she was a homeless, single, working mother caring for five children in a punishing urban wilderness.

Five years later, in the fall of 2023, Evelyn sat down in a small office meeting room to tell me her story. I had connected with her through outreach to a transitional housing organization called Door of Hope, which supported a small family shelter network in Pasadena, a neighborhood northeast of Los Angeles.

My reasons for undertaking to write a book about her journey were powerful. Yet, at this early stage of the process, I was still having trouble clearly articulating them.

Much of my work to that point had focused on schools and education, and I was interested in learning more about the support systems available for school-aged children experiencing housing instability.

The city’s current data stated that there were roughly ten thousand students in the school district facing this plight. Actual school administrators and educators believed that the number was far higher.

This dissonance felt profound on its own, because it meant that many families were avoiding—perhaps even hiding from—official service providers.

Whenever I picked my own two kids up from school and observed all the students moving in clusters or alone down the sidewalk, I would strive to imagine what it might look like and feel like to be a young person.

Someone who, after a seven-hour school day spent among peers learning about math and contending with hormones and stressful social dynamics, did not have a home to which they could return.

The tremendous, perhaps even impossible resilience that such a life would require is what drew me toward Evelyn’s family and the book that would eventually be called Seeking Shelter.

Evelyn’s Journey With Homelessness Was Over When I Met Her

When Evelyn agreed to meet with me for the first time, she had recently graduated from the Door of Hope program and had been living in her apartment for a few months. She had taken some professional classes and had procured a clerical job at a nearby accounting firm.

Her kids were all thriving in school. But her days were stressful, and she clearly did not have time to sit with me and talk about her experiences—yet she had made the time, anyway. That very simple act of generosity was actually astonishing to me, and I expressed that.

Evelyn shrugged and said that having five kids took up one hundred percent of her time and emotional bandwidth.

However, she still managed to accomplish a lot with the remaining zero percent: work a full-time job, volunteer at her kids’ school, cook, go to church, and meet an author.

We would ultimately spend nearly one hundred hours together revisiting the big and small moments of her and her children’s survival of the pervasive homeless crisis in Los Angeles.

My Life Trajectory at the Time

While I typically try not to bring many of my concerns into my book research conversations so that I can focus completely on the people generous enough to permit me to write about them, during that period of my life, it was quite difficult to compartmentalize some of the turmoil in my mind.

I didn’t know it then, but Evelyn’s story of saving herself and her kids would also save me in a way.

At that moment when she and I first met, I was forty-two years old and had been sober for two years. Sobriety had not been a struggle to maintain since early on. Very simply, the new lifestyle was necessary for me to accomplish what I desired to accomplish as a father and a writer.

Yet in the time since, some previously vital friendships had faded away, and the rhythms of my marriage had reconfigured in confusing ways. Most typical adult social gatherings—school functions, holidays—felt like chores.

The running habit that grounded me was probably starting to border on neurotic, and I was beginning to doubt whether I had any aptitude in coaching youth sports or writing books—two great joys of my daily life.

I was a present and engaged father with the capacity to be a positive influence on my two kids. Yet as they edged toward teenagerdom, I spent so much time pining for the simpler past that I was beginning to miss some of the wonders of the current passage.

In short, when I met Evelyn and endeavored to craft a narrative founded on her miraculous perseverance and love, I was personally adrift. Much of my energy, day to day, went into hiding what a mess I was.

Seeking Shelter and Exploring Evelyn’s Homelessness

In the book project, entitled Seeking Shelter, I wrote about Evelyn’s journey of keeping her kids in the school while homeless, thusly: “Survival is not clean or elegant; there is no music to it, no pageantry, no accolades; it does not follow straight pathways or hold pauses for rest or reflection; it does not feel fulfilling or noble, strengthening or cleansing, spiritual or redemptive. There is no immediate reward, no effortless landing on the other side. Survival is a scary, humiliating, ugly threshing of the body and the soul.”

During their three years without shelter, Evelyn and her children avoided the city’s family service system. She had heard dozens of stories of mothers like her seeking help on desperate evenings and, as a consequence, having their kids taken away before morning, shunted to foster care.

Instead, Evelyn found below-board housing situations for weeks or months at a time. She relied heavily on a program that provided emergency motel room vouchers after workday hours when space was available.

Often, these rooms might be located two hours away across the vast city or in unsafe neighborhoods, filled with unsettling people.

When she had no other options, she and the kids all slept together in her 2009 Toyota Highlander SUV. Evelyn always stayed semi-awake in the driver’s seat in case she needed to peel away from potential danger, such as a predator or police officer.

She would place a single flower in a plastic cup of water on the dashboard as a home-like flourish.

Throughout these years, she dropped her kids off at school each morning, worked restaurant shift hours at Applebee’s, picked them up, and hoped for safe passage somewhere through the night.

Wherever that might be, including their car, she helped them with homework, school projects, and talent show rehearsals. At community rec centers, she signed them up for baseball teams and dance classes.

On weekends, they went to the city’s parks, beaches, museums—anywhere they could be together, for free. She did her best to ensure that her children experienced her as caring and devoted, even when their situations were chaotic and destabilizing.

Resilience Helps When Life Is Unstable

Resilience is difficult to measure even in its most pronounced manifestations.

In this family, over a prolonged stretch of helplessness, and in a society whose structures made asking for even the simplest provisions a tremendous risk, resilience was relegated to the smallest of moments: giving a hug to Mom when she needed one most; telling a story that made everyone laugh before falling asleep in the back of an SUV, splitting a scoop of ice cream six ways, giving up individual wants to meet family needs.

For the first few months of regularly meeting with her to record her memories and begin writing my book, I remained oblivious to how the wisdom she was imparting might apply to my instability.

Failing to make that connection was probably a willful one, because doing so promised a great deal of interior work that I wasn’t prepared for. Indeed, I hadn’t even admitted to needing it because the resilience required to recover would be substantial.

A much easier tactic would be to minimize my personal travails and carry on with my head down and my focus narrow.

The directive to stop avoiding and try to be a more productive participant in my own life came not from a revelation, or a therapist, or a book, but from Evelyn herself.

There Will Be A Point In Your Life When Something Is Beating the Hell Out of You

At a certain point, after sensing some undercurrents of my demeanor over a period of time, she said, “There’s something beating the hell out of you inside, isn’t there?”

I asked her if it was truly that obvious. She replied that to her, it was. I gave her some of the broad details of feeling physically and mentally wonderful, but emotionally disconnected.

I told her about myself sheepishly, because she had contended with so many more urgent and deadly problems herself. But she listened as a caring friend would.

“Did you ever hurt anyone you loved when you were drinking? Like, physically?” This question seemed paramount to her, a deal-breaker. I assured her earnestly that I hadn’t, that alcohol had rendered me passive and distant when I’d relied on it as a crutch.

My problem was that now, as a sober person, I was also acting passive and distant. So, I was scared that this was just how I was and that I would struggle to connect with my kids as they grew up.

Evelyn looked at me as if I were a fool. She said, “You’re kind of an awkward person, for sure, okay, that’s not like a bad thing. But you love your kids; I can tell by how you look when you mention them. And obviously, I know you listen to them because of how you listen to me and my kids. So trust me, you’re fine.”

Then she repeated a mantra that one of her own closest mentors in the transitional housing program would say to her during down moments: “You just have to finish well.”

Evelyn herself had needed a great deal of time to learn how to slow down and think intentionally—unfamiliar acts to her due to the nature of survival in a society that often interprets poverty even for young children as a supreme character flaw.

Adopting them now was making for its own form of resilience and perhaps defiance. In taking the time to draw me out, she laid a parallel roadmap that I would rely on in the months to come and that still today, as I write this, rings true: love, listen, and finish well.

JEFF HOBBS – Award-winning author, professor, and speaker based in Los Angeles, Jeff Hobbs is a New York Times bestselling author who explores complex sociological topics such as access, entitlement, racism, classism, justice, and identity in modern day America. Hobbs’ notable works include The Short and Tragic Life of Robert Peace (now a major motion picture), Show Them You’re Good, Children of the State: Stories of Survival and Hope in the Juvenile Justice System, and more. His most recent release, Seeking Shelter: A Working Mother, Her Children, and a Story of Homelessness in America, is available now.

0 Comments