Trigger Warning: This story addresses childhood sexual abuse.

Stories profoundly influence us, including the stories we tell ourselves. They shape our thoughts, actions, and world. As we go through our days, we construct narratives about our interactions, what we see on the news, and about ourselves.

We tell tales about our past, present, and imagined future, which often run automatically, informing our lives in countless ways. The stories help us make sense of our lives, process new ideas and events, and provide us with cognitive comfort and ease.

They also allow us to cultivate our identities and inform how we dance through our lives. We habitually see others and the world through our constructed narratives and lenses.

Why the Stories We Tell Ourselves Matter

People view themselves as the main characters in their own stories. Although these personal narratives significantly impact our own and others’ well-being, we may not take the time or energy to examine them.

We employ numerous cognitive distortions, including paying closer attention to what confirms our beliefs, feeling discomfort with cognitive dissonance, and engaging in various fallacies when constructing our narrative identity.

Narrative identity encompasses the personal, continuously evolving story we weave to imbue our lives with meaning and coherence. It’s a crafted selection of past memories and future aspirations that illustrate the journey of how we became who we are and hint at the potential directions our lives might take.

Narrative identity development, which starts in late adolescence and early adulthood, is an ongoing process. It allows individuals to shape and understand their own life story and the concept of human personality.

However, we tend to prefer coherent narratives and may impose a false order on otherwise chaotic events. Our experiences and identities impact our interpretations of the world and the tales we tell about our own lives, selves, and others.

What if we challenged at least some of these narratives? How would that alter how we view and treat ourselves, others, and the world around us?

We Derive Meaning From Narration and Literature

As an educator with a passion for reading, I taught my students critical literacy practices to use with texts they encountered.

They learned to consider why an author may have written a particular piece, messages conveyed through word choices, which voices and perspectives have representation, the political and social ideas embedded in the document, and so much more.

They also examined the impacts of the lenses through which they viewed and read the world.

Critical literacy became second nature to me and many of my students. What pertains to a piece of text may not transfer as readily to daily life despite its applicability. I knew how to use these skills, but how often did I apply them outside of texts?

Unfortunately, I did not do this consistently. I used critical literacy lenses frequently with news stories, literature, movies, etc., and examinations of the single stories or other narratives I held.

However, I used it less when trusted people would tell stories and rarely on self-narratives.

Look Out for Narrative Fallacy in the Search for Our Narrative Identities

Before I started my healing journey about a year and a half ago, I paid little attention to the many narratives about myself and my life that ran automatically in the background of my mind and impacted my physical and mental health, as well as my worldview.

Honestly, I didn’t like myself much.

I saw myself as irreparably damaged by the childhood sexual abuse and the vengeance campaign launched by the upper elementary teacher after I told on her for molesting me.

I internalized some of the cruelty, telling myself that I was a failure, that I did nothing right, that I would never be successful, and that I deserved to be treated poorly. Children, including teens, tend to adopt their caregivers’ voices.

This extends beyond parents/guardians to other important adults in a child’s life, such as teachers. Children may also adopt the voices of peers and others who bully them and speak to themselves in the same manner.

Although I’ve fallen short and epically failed at times, I do my best to see beyond behaviors to the child or adult under the behaviors; all behavior is communication. When words fail or cannot be found, behavior shows unmet needs.

Move Beyond Labels

People tend to label behaviors as “good” or “bad,” when what they truly mean is “conforming” and “not conforming” to expectations.

They often then go on to label the person as “good” or “bad” instead of working to understand the meanings behind the behaviors; these labels correspond to stories they’ve heard and expressed to themselves.

For example, the child sobbing and yelling on the ground may feel overwhelmed by stimuli and not know how to manage it. Labeling this behavior and/or child as “bad” harms the child.

However, looking at the unmet need and doing one’s best to resolve it helps the child.

Storytelling is an Integral Part of Understanding Human Life

Humans have an innate longing to be seen and heard as we truly are, not just through the lenses of the stories that others communicate about us and people like us. We are unique individuals, shaped by and forming our views through stories.

Each of us can choose whether we use the tales we tell to uplift someone, including ourselves, or whether we miss opportunities to have positive impacts.

We can also examine our responses to people and events and change the stories behind those reactions.

I try to use my intuition and experiences to shape the ever-evolving stories I tell about others. I look for someone’s strengths, which provide a firm foundation for growth.

Given how horrible I felt when the abuser and her enablers retaliated against me for years, I go out of my way to try to build people up.

I do not want anyone else to feel as I did. Although I have failed sometimes, I strive to learn from them and make amends when possible.

In order to change my behavior, I examine and alter the narrative I held that caused the failure. I have also frequently positively impacted someone, even if only for a moment.

Love has always been a cornerstone of my worldview; my experiences have made it even more essential.

Knowledge and Self-Love Play an Important Role in Healthy Narratives About Life

Yet I denied myself that same love. Once I became aware of that, I asked myself why. I excavated the origins of each deeply embedded belief I held about myself as I stumbled across it.

Many negative beliefs germinated or grew more entrenched through the abuser’s and her enablers’ retaliation after I told on her.

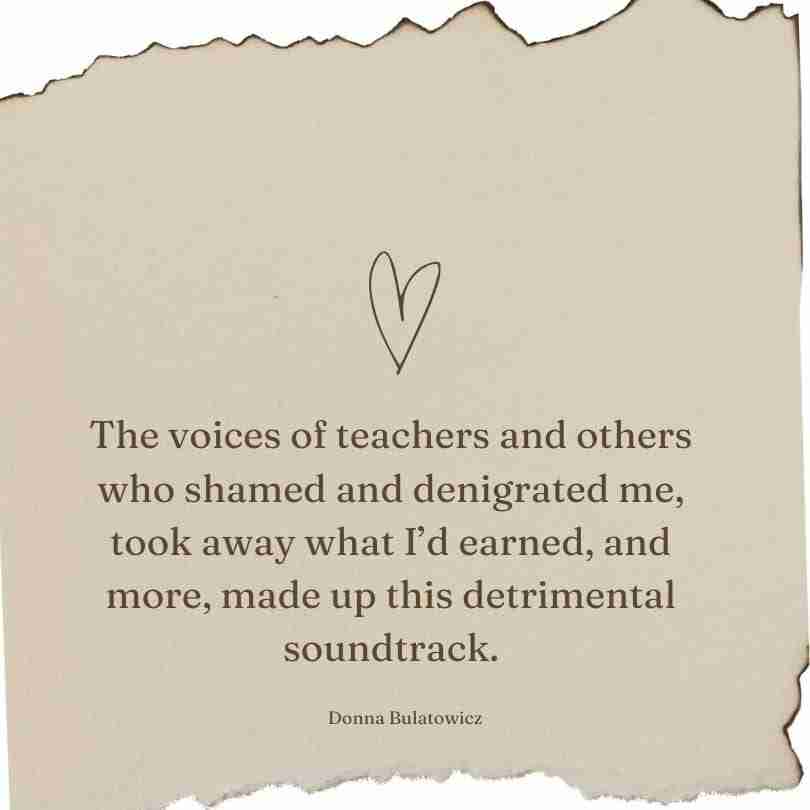

The voices of teachers and others who shamed and denigrated me, took away what I’d earned, and more, made up this detrimental soundtrack.

Interwoven with them, I could hear the softer voices of those who stood up for me quietly, like the teacher who confiscated the papers my abuser passed around that trashed me or the teacher who lent me books by and about other survivors.

The words of others play a role in our self-narratives

They tacitly let me know that someone believed me and saw me rather than the story the abuser invented about me to protect herself from the consequences of her actions.

Having someone see you when you’re a child drowning in a turbulent sea of gossip and retaliation is a powerful feeling.

The teachers who ignored the rumors and looked at the quiet, polite, diligent girl in front of them provided a lifeline for a sinking teen and kept my self-narrative from completely destroying me.

When adults treat a child poorly, that child may turn the cruelty they receive upon themselves. I know I did, even though I couldn’t make sense of their actions.

When I learned about the papers being passed around about me and what they contained, I constructed a more accurate narrative, though I will never know why they chose to protect an abuser and further traumatize a girl.

I still do not understand how they latched onto the mirage of lies that the abuser fashioned to protect herself from having any consequences for sexually and otherwise abusing me.

A Self-Narrative Can Impact Many Life Stories

What stories did the enablers tell themselves? How did they justify taunting a child in front of the class? What was going through their minds as they yanked away honors that I’d earned?

Why did they feel sabotaging my chances for scholarships was acceptable? Which narratives did they spin about me that enabled them to ignore logic and reality?

I consider how different my life and my world would be if the enablers had chosen to take what the abuser said with a grain of salt—or simply chosen not to let it impact how they treated their student.

Although I would like to know whether they questioned why the abuser passed around papers to my teachers about me, I most likely never will.

However, I ponder how they might have behaved differently if they had asked themselves why an adult had such a vendetta against a child.

Or if they had wondered whether an innocent person would work so hard to spread maliciousness, especially when the girl in front of them reflected nothing contained within the reputation-destroying rumors.

But they didn’t see me; they saw the false stories they had been told

These enablers did not appear to have considered how incredibly rare it is for a child to lie about sexual abuse or how frequently child molesters lie when caught (nearly always).

I doubt they considered how unlikely it would be that I could describe typical behavior for an abuser, know how two females have sex, know details about sex, and more unless I experienced sexual abuse.

This all happened in the pre-internet days in a fairly homophobic area. The enablers also did not appear to have noticed the discrepancy between the behaviors described in the documents passed around and the girl they encountered.

She followed rules scrupulously and stayed quiet, shrinking into herself with each emotionally abusive word or behavior from her teachers.

Research has shown that once we establish an opinion about someone, cognitive bias steers us to interpret their actions and character traits in a way that reinforces our initial perception.

This tendency to favor information that supports our pre-existing beliefs over new evidence reflects our natural inclination to avoid the ambiguity and challenges presented by unfamiliar concepts.

It Takes Wisdom to Overcome These Aspects of How Our Brain is Wired

Many of the rationales that I heard from the enablers and others were based on stereotypes, the halo effect, and other fallacies. The police and others said that “a woman wouldn’t molest a girl.”

Others said things about how she didn’t abuse them, that no other girls in the same class said they were molested, that she did very good things as a teacher, that they never saw her abuse me, that she wasn’t affectionate, etc.

Embedded within these false assumptions are stories that they must see something for it to have occurred, that everyone sees all sides of a person, that a child molester abuses every child they encounter, and that people who do good can’t also do bad (and vice versa).

They chose not to examine these underlying narratives to see the fallacies contained within.

Lack of questioning the stories we construct, hear, and repeat can also create false dichotomies of us vs. them. Our brains make snap decisions based on our narratives.

We also determine who we feel is “like us” and “unlike us.”

If we other someone, we may deny their humanity, allowing us to engage in crueler acts than we may have otherwise, all the while justifying the damage we do—just like the abuser and her enablers did.

They dehumanized me and listened to tales full of lies.

This taught me multiple lessons at an early age, including how words can slice us and impact how we interact with others.

Consider how your words and actions may impact the evolving story that someone holds about themselves, especially when that person is a child and/or you have power or feature prominently in their lives.

You Can Become a Better Person by Telling Yourself A Different Narrative

This lesson extends to our current world, where social media increasingly isolates us in silos. It becomes easy to think in false binaries, and it’s dangerous. We need to dismantle polarizations rather than feed into them.

We have more in common than we may think at first, and critical questioning of the stories we hear and tell can lead us to recognize the humanity within another. All of us contain a myriad of parts, identities, experiences, and beliefs that shape us.

Giving each other grace and questioning what we say to ourselves and each other can lead to more collaboration and less dehumanization. One encounter with someone or viewing one part of them does not constitute the whole.

When you come across a story that reinforces what you already think, take time to question those thoughts. Whose perspectives are you listening to or not listening to?

If the story paints a single image of a group of people, question it, as no single story can capture the complexities of even one person, let alone a group.

Remember, Past Events and the Stories We Tell Ourselves do not Define You

If you hear something negative about someone, what else do you know about that person? What else have you seen, heard, experienced?

Are there other motivations the storyteller might hold? What biases, lenses, and more inform the tale? What perspective is missing?

If the enablers had taken the time to consider these questions when they read or heard the falsehoods the abuser spread, they might have treated me very differently.

Yet, had I not experienced the backlash from the enablers, would I have developed the same level of love and compassion I currently have? Would I see the world as I do? Would I actively interrogate the stories I hear and tell?

Probably not to this extent, if at all. That means I wouldn’t be me. I have learned to love myself and love who I am becoming.

We would love to hear your thoughts on the stories we tell ourselves in the comment section below.

Powerful read thank you

Thank you for reading it!