Breaking Free from the Single Story: Why Your Full Truth Matters

Mrs. Smith is a pseudonym.

“A woman wouldn’t molest a girl,” the officer scoffed, tossing down his pad and pen. “And Mrs. Smith? She’s married. Has a husband and sons. Why are you making up these accusations?” He believed in the single story of who a predator is.

I stared at the officer in disbelief. Once again, my assumptions about the world had been shattered. Right then, I knew I could not protect other little girls from Mrs. Smith.

“I should have kept my mouth shut,” I thought. “Now I’ve pissed off the police and Mrs. Smith and hurt my parents and others.”

I was just a little girl and didn’t know that the officer’s ignorance and bias were to blame, not me. I took on the blame and shame he and his colleagues readily dished out.

Just as I had taken on the blame and shame of the abuse. I also took on the blame for my parents’ devastation at hearing that my teacher had abused me, and that was the reason behind all my behavior and personality changes.

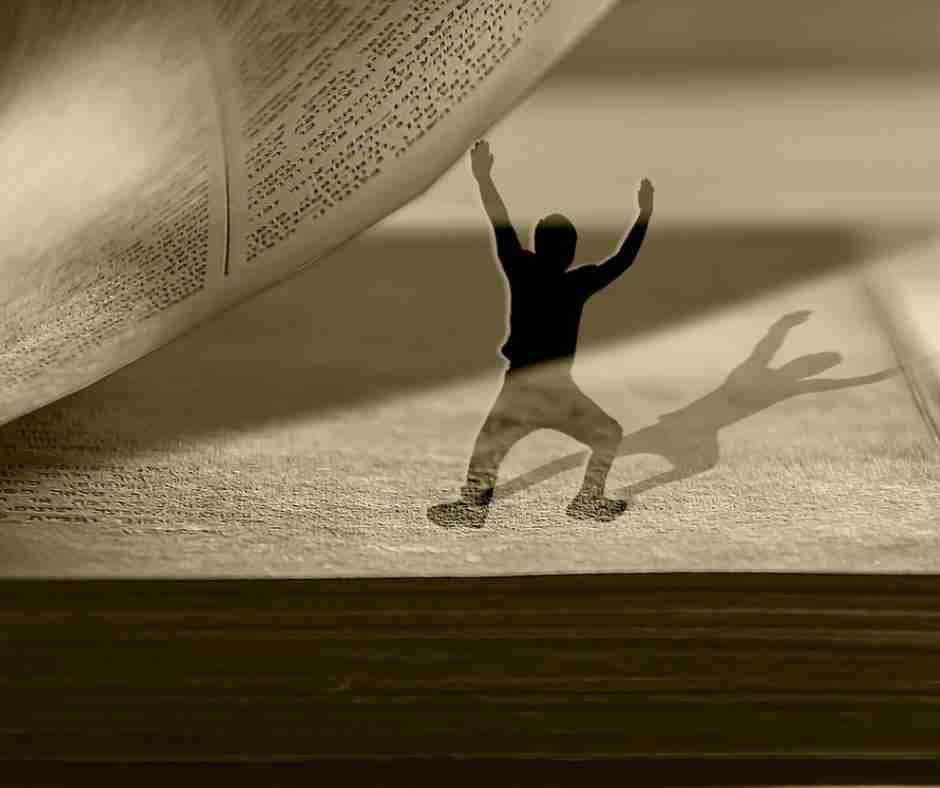

I didn’t yet know the power of a single story.

The Single Story Creates Stereotypes

To paraphrase Chimamanda Adichie’s TED Talk, there is the danger of a single story (paid link) being the only one you hear.

The single story tells us who should be seen and who should be erased. It tells us who should be heard, valued, believed, trusted, and much more. It robs people of their truths.

Single stories function to maintain social hierarchies and enforce oppression. We all absorb single stories from everyday life.

We cling to these unknowingly until something challenges those single stories and prompts us into reflection—if we choose to reflect and adapt our views.

There is a single story about who is most likely to be a pedophile. This story has changed some in the decades since I was a little girl, but many people still think of a creepy man who has no redeeming qualities.

It startles people when a child molester is a woman or a person who is charming, popular, a pillar of the community, a teacher, etc. Sex offenders who don’t fit the single story are more likely to get away with their hideous crimes and harm more children.

The single story of the victim is one of a white girl who a man molests. This victim follows rules, doesn’t get angry, pleases adults, resists the abuse, tells immediately, has physical evidence, and shows the “appropriate” amount of emotion when telling on the abuser.

She isn’t dissociating, crying too much, showing no emotion, telling too much detail, or otherwise making adults uncomfortable with what was done to her. This single story erases most victims, as no one is perfect.

Those who don’t fit this one story are less likely to be heard or get justice, especially those who were abused by a woman or those who are boys or nonbinary people.

Single stories erase nuance and personhood. They flatten people to stereotypes and can cause great harm, particularly when those in power fall for the single stories and dismiss another’s reality and equal humanity.

Molestation Leads to the Default Position of Loneliness

When the police let Mrs. Smith get away with her crimes, as most sex offenders do, I felt utterly alone. I didn’t know where to turn or how to talk about what Mrs. Smith had done. I felt like people wouldn’t believe me because I was a girl and she was a woman.

Some people believed me, such as my family and most of my classmates, many of whom had seen Mrs. Smith behave inappropriately with me. They even teased me about being her girlfriend. However, the ‘injustice’ system didn’t believe me.

Others didn’t believe me simply because neither Mrs. Smith nor I fit the characters of molester and victim in the only story of abuse they heard. My story was an entirely different story than the single story they were familiar with.

Mrs. Smith quickly started her vengeance campaign. Immediately upon returning from the suspension, she told her students that it was because I had lied about her. She encouraged them to let me know how they felt about what I’d done.

She lied to my current and past teachers, telling them I was crazy and ruined lives. Mrs. Smith did this every year through my first year at university.

I felt I couldn’t trust any of my teachers. Some teachers were very unkind to me and prevented me from receiving honors and other achievements I’d earned. Others were distant. Some were kind and treated me like any other student.

But I mostly felt isolated and lonely. Stories matter, and the one they heard about was inaccurate, defamatory, and cruel.

However, it may have fit the definitive story of abuse they accepted. My story was silenced. It, and others like it, are exactly the kinds that need to be shared to rewrite the dominant narrative that benefits abusers rather than victims.

I searched desperately for another story like mine, hoping to find someone else who had been molested by a woman. There were stories of boy victims, but none about girls. I felt even lonelier. How could I be the only one?

Repairing Broken Dignity and the Healing Power of Community

I wasn’t the only one, though. It’s just a story that often remains taboo and invisible. When I started my healing journey several decades later, I realized just how many stories like mine existed.

However, those stories are often hidden and not a part of the narratives people share. Most of the stories I came across were in survivor groups I joined.

There are some books that include examples of women abusing girls. I treasure these relatively rare moments when I feel part of a community, albeit one none of us chose.

Hearing that other women had been abused by women helped me feel seen and validated for the first time since before being abused.

Community is healing. I once attended a retreat for women survivors. I started sharing my story with others. Each time I shared part of my story, some of the shame lifted.

Being heard is healing. It counteracts the loneliness forced upon me during the abuse and after I told. I feel more seen, heard, supported, and loved than ever.

Countering The Single Story

Single stories can take a while to overcome. They are insidiously woven into societal frameworks. However, we can combat them a little at a time. It heals me to tackle single stories and get others to see beyond them.

I tell my story in many places, such as podcasts, radio shows, magazines, websites, social media, and StoryCorps. I have created and am redesigning training for teachers and other education professionals using research, stories, and more to counter the existing single stories.

Additionally, I am working to fill in gaps in the literature and more. I do not want anyone to feel as isolated as I felt.

Telling one’s story is crucial to negating the single stories in the world. Each of us can use our experiences and words to reach out to others and show them they are not alone.

We can expand our own and others’ understanding of the world when we listen with our hearts and minds and truly see another.

There is great courage and compassion in vulnerability. Together, we can change the world, one story at a time. (Take a few minutes and watch our full interview with Donna on our YouTube channel.)

The Danger of a Single Story Robs People of Their Power

Adichie asserts that media and literature available to the public often only tells one story. This leads people to generalize and make assumptions about groups of people. Then, the reader has well-meaning pity for those who fit the popular images of that group.

The possibility that there is more than the one thing they know of clouds their perspective.

Complex issues like sexual abuse and child molestation are hard enough for people to talk about. Stories matter whether you write or talk about them. Don’t let someone else’s perspective of the characters who should be in a story negate what you went through.

I realize now that my story is an example of a different look at the incomprehensible people who commit these acts against children. Maybe, when this happens to another little girl, the person she tells will have seen my story or other stories like it. That police officer or administrator won’t be committed to the stereotypes society has created.

Tell Your Story And Listen to The Stories of Others

In her TED Talk, Adichie explains how media and literature often tell single stories, which can perpetuate and reinforce stereotypes. Single stories can also lead to false assumptions about groups of people and impact how individuals, communities, and societies treat people, especially those whose stories contradict the dominant narrative.

Thus, the single story can impact how survivors of childhood sexual abuse are viewed and treated.

It’s challenging to talk about childhood sexual abuse. It is difficult to fathom that someone would harm a child, and it’s uncomfortable to discuss, especially in a society that tends to shy away from open dialogue about sex, sexual abuse/assault, and more.

As different parts of the U.S. enact curricular restrictions, they politicize accurate, inclusive sex education, sexual abuse prevention, and anything that challenges the dominant single stories. This creates a greater atmosphere of fear, leading to more silencing of voices and groups contradicting the majoritized viewpoint.

In this current climate, reclaiming my voice and telling my story took courage. I have realized that my story challenges various single stories that people hold about women, girls, and sexual abuse.

I share it so my story can help others who have had similar experiences, help those in power to see that abusers and victims don’t always fit a particular stereotype, and inspire those in power to believe the counter-stories that are being told.

Embrace the Counter-Story and Your Voice

Stories matter. Tell your story when/if you are ready, especially if it goes against the prevailing narrative. Your voice matters.

Your story is needed. Additionally, seek out counter-stories—those that differ from the dominant single story—through books, media, and other places.

Life and people are complex. There is much we can learn from counter-stories and other narratives. Someone is waiting to share their story and reclaim their voice, power, and sense of self.

Remain open to listening compassionately when others talk.

Be open to the possibility that there is more to the story than one version of it can ever encompass.

We all have different perspectives, lives, personalities, and more. The more we are open to possibilities and to each other, the more we learn and grow, and the more we help people feel seen, heard, valued, and believed.

You are worthy. You are valued. I believe you.

Thank you for bravely sharing your story and explaining the single story narrative!!

Her story was heartbreaking, but I imagine there were many people who needed to hear it. I also learned so much more about the single story narrative. Thanks for leaving a comment!