Written by Blair Sorrel

It might be high summer—when life gets languorous and much of France goes on vacation—but for the schizoid subculture, not much changes. We marginalized endure an existential blur season after season. The challenge: how to tap one’s inner core and untested resilience to achieve stability when a paycheck won’t.

There I was, marooned on one of the world’s leading commercial islands, New York City. Lured by a universe of publishing opportunities, I followed the conventional post-Smith College career path right to the Big Apple. My entry-level job at Working Woman magazine led to many other lowly stints, all going nowhere slowly.

I gravitated to the New York Department of Labor’s Worker Career Consortium, which I dubbed “The Center for Lifelong Learning.” Many of its tenured loitered far longer there than in any other office.

But I couldn’t work. Undiagnosed schizoid personality disorder made my best laid plans untenable, same as it upends even the most qualified candidates and work ethic. And the twin evils, unemployment and underemployment, assured plenty of other U-turns along the road to professional failure and despair.

So Much for Corporate America

I was a copywriter, decorator, tour guide—all half-hearted efforts to reinvent myself. But I effectively fired myself from Corporate America before they could axe me. I hoisted my copywriter portfolio (which I refused to show to agencies) timorously as the ultimate white flag.

Given my losing proposition, I would have shamed Frank Sinatra. So much for “If I can make it there, I can make it anywhere.” One of Nietzsche’s “the botched and the bungled,” I realized I would be productive or idle depending on how I structured my days.

From an Undiagnosed Schizoid to Unsung to Overbooked

Then, I was diagnosed with schizoid personality disorder—and it all made sense. I turned from self-imposed isolation to selflessness, joining the legions of unsung pro bono laborers—heroes who log hours without remuneration, recognition, or even transportation reimbursement. And I started giving in to downtime—but that didn’t mean being down and out.

I read. I didn’t rely on others’ company. And I combed The New York Times’ event calendars, but not as most would. In those columns, a calling came a-calling: Decorator show houses needed room monitors. Nonprofits searched for envelope stuffers. A receptionist was required here, a coat check there.

It all began to add up—a hidden market of opportunity. Health and beauty aids’ product testing, soft restaurant openings, market research studies, hair model cuts and color, and film screenings proliferated.

All begged for participants, and I was poised to write about them. Remember, this gratis bounty was sub rosa before the advent of the internet. My off-the-job experiences became copy blocks, then a column for The Resident and Free Time magazine. “The Dollarwise Dilettante” was born.

For seven long years, I canvassed Gotham’s retail and commercial freebies for my dedicated readership. I had the town wired. Even at my most impecunious, I lived like a queen. My way became their way; my voice, their choice. I even garnered paid subscribers!

The publisher, Natella Vaidman, prevailed upon me to make my postings upbeat and, if possible, droll. But churning out 25 leads a month, I began to feel the inevitable wear and tear. “There will be people there,” Selma Landisberg, my clinician, reminded me, and I’d enter a room or assembly as if the floors were land mines.

If I dithered in faxing in my monthly copy, I steeled myself for reprovals.

Giving Back: A Better Track

St. Augustine espoused service as perfect freedom. Toting John Bradshaw’s Healing the Shame that Binds You for moral support, I dug into the Volunteer Referral Service’s binders and became a valued staffer of sorts. Collating packets at the local MS Chapter on behalf of my sister’s diagnosis, I was even offered a job.

Relocating to Merrimack Valley some years later, I settled in Lawrence, one of New England’s poorest communities. I felt at home with the planned industrial city’s hospitality and good neighbor vibe. The town had exceptional social services but also high homelessness, drug addiction, and disability. I discovered the soup kitchen Bread and Roses.

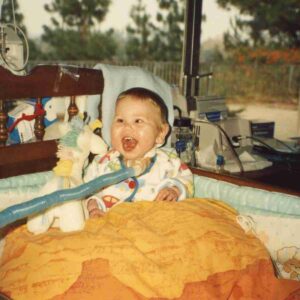

What is the face of need?

A beaming Brian and his baby. Or a recharging Ralph, ready for his coffee refills. Maybe a jubilant Jeanette celebrating with her freshly baked birthday cake.

Like me, they rely on this near-daily dinner not just for the hearty repast but for moral support. More than a “mess hall,” it’s a transformative experience for the struggling. The weary, the wary, and even some workers converge nightly and leave fortified for the next challenging day.

Whether we sup in silence or commune in chatter, we’re all met with hospitality as bright as the fluorescent lighting and peripheral floral decorations.

Beyond the pastries, trinkets, or holiday duffel bags fraught with chilly-weather essentials, this cozy nexus vivifies us.

The two Sues, Tony, Horse, Lauryn, Nilly, and Sarah—among other dedicated staffers—are invariably warm and welcoming. They don’t judge or patronize, no matter how trying their shift may be. All of us, the servers and the seated, are improved reciprocally.

Where there’s hope, there’s a second helping. Starting at 6:30. Where there’s a helping hand, there’s this local refuge that deserves a hand. Where there’s Bread and Roses, there’s for many a reliable supper—and for some others, the sustenance of a second act.

Blair Sorrel is an author, innovator, and animal lover. She was Free Time’s “Dollarwise Dilettante” columnist, Together Dating Service’s matchmaker, and New York Blood Services’ apheresis recruiter. She founded StreetZaps to protect dogs and people from stray voltage, and was the first community representative invited by Con Edison to their annual Jodie S. Lane Stray Voltage Detection, Mitigation, and Prevention National Conference. Her memoir is A Schizoid at Smith: How Overparenting Leads to Underachieving.

0 Comments