When we talk about the immigrant experience, we often start with the moment someone steps off the plane.

However, the immigrant experience is rarely a straight line—it zigzags between survival and dreams, between heartbreak and hope.

For me, that path began in Baghdad, where I grew up glued to a television screen watching American cartoons like Looney Tunes while warplanes droned overhead.

Iraqis were tired physically, mentally, and economically, and had lost many family members, relatives, friends, and neighbors to the war.

My parents did everything they could to shield us from the chaos. Comic books were especially sacred.

When the power went out, we’d color in the light of a kerosene lamp. And when the electricity flickered back, the TV would come to life with subtitled versions of G.I. Joe, He-Man, Thundercats, and Voltron.

Growing up in Iraq in the 80s wasn’t glamorous or even as nostalgic as Stranger Things portrays it to be, though, in its defense, it is set in the U.S., not Iraq.

Part of me always thought the grass was greener on the other side, given Iraq’s conditions while I was growing up.

That belief, against all odds, to Billings, Montana—a place I never imagined would become home.

Growing up as a Child in Baghdad

When I was a kid, Baghdad was not the romantic version of ancient Mesopotamia you see in textbooks.

It was the 1980s, and Iraq was in the middle of an 8-year war with Iran. Saddam Hussein had taken control, and the economy, once thriving, began to unravel.

Families like mine clung to small comforts. Power outages meant it was time to pull out comic books or play games outside when it was safe to do so. But when the power came back, we turned on the television.

That’s when I met Bugs Bunny.

Not literally, of course.

However, in the way kids latch onto characters that feel like friends, Looney Tunes became my portal into another world.

Bugs Bunny didn’t just make me laugh—he showed me a world where rebellion was clever, not dangerous. A world where a smart mouth could outwit brute force. A world far removed from the one I was living in.

That irony stuck with me, and so did that dream of something more.

The sass of Daffy Duck, the resilience of Wile E. Coyote—was American idealism in a 30-minute slot, subtitled in Arabic but impossible to misunderstand.

The characters were wild, hilarious, and determined.

They got flattened by anvils and sprang back to life. Maybe that’s what hooked me most: they never gave up.

I Faced Difficulties as a Child Among My Community Members

At school, I struggled to reconcile what I saw on screen with the society I lived in.

They say kids have spongy brains, so you begin to mimic the language, behavior, cultural norms, and ideologies of the characters you like and look up to.

By the time I was in 5th grade, I was reciting cartoon catchphrases in class, only to be corrected by teachers who insisted on Oxford English.

I wasn’t just learning a language; I was living a contradiction. The more I embraced American media, the more my culture clashed with it.

I felt like a square peg in a stringent, traditional society.

The divide only deepened in the 90s, after the Gulf War. U.N. sanctions crushed Iraq’s economy, and Saddam’s paranoia tightened its grip on daily life. But American pop culture still seeped in.

Freedom, choice, and self-determination were all popular messages of the shows I watched. I didn’t have words for it then, but I was already dreaming of a different life.

One where being different wasn’t dangerous.

So, I kept watching. I kept learning. And deep down, I started hoping.

Hearing From Other Iraqi Americans

We all know the angst that comes with being a teenager. Mix that with Saddam Hussein’s leaning more and more into tyranny and Iraq being under severe sanctions by the U.N. Let’s just say, no music genre was left unturned during that phase!

Then shows like Xena: Warrior Princess, Charmed, Buffy the Vampire Slayer, and Beauty & the Beast started to arrive.

While fictional, the ideals were the same about good versus evil, the meaning of home, love, sacrifice, loyalty, patriotism, right & wrong, etc.

Movies, fictional or not, carried the same tones. Then arrived the Yahoo chat rooms, Myspace, Facebook, and the ability to Google anything.

That’s when I finally got in touch with the troops on the ground, so to speak.

All this time, deep down and in the back of my mind, I’d fantasized about leaving Iraq for good. Not for a lack of loyalty, but because of the continually declining conditions and the inner cultural clash I was experiencing.

Some extended family members had managed to escape after ’91. They wrote letters warning us: “It’s not what you think it is.” But I didn’t believe them.

I thought they were being selfish or maybe afraid to jinx their success.

I held tight to the image in my head—the America of cartoons and sitcoms, of music videos and Yahoo chat rooms. It was shiny. It was safe.

My Visa Came in the Form of College and Education

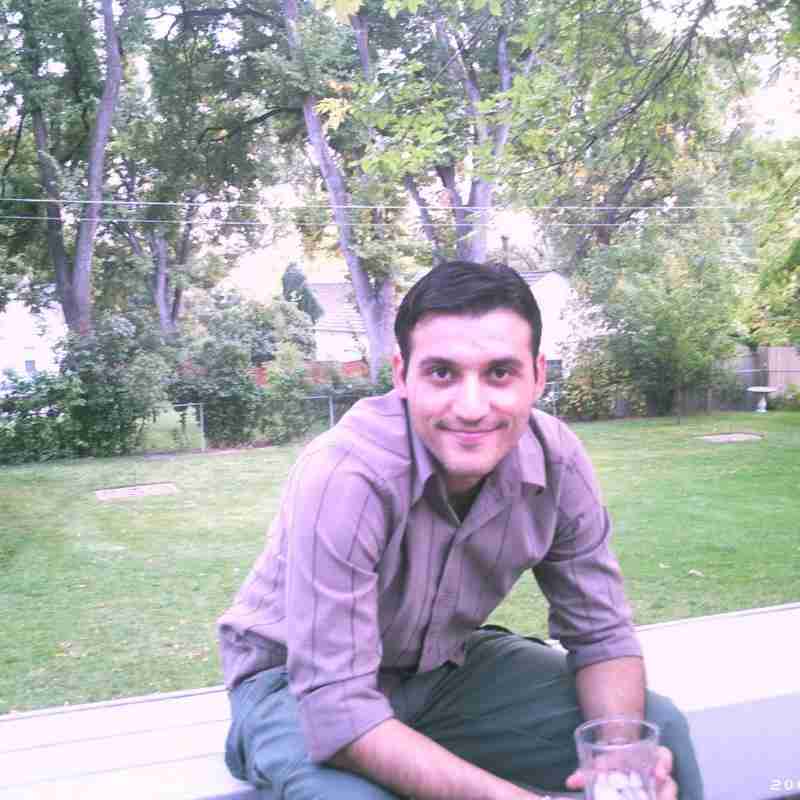

In 2006, I got my chance. Through a Fulbright scholarship, I landed in Billings, Montana, to teach Arabic for 10 months. I came for the experience.

This was not the way I thought I’d leave the country.

I was looking at this trip as a taste to give me some global experience so I can be more marketable when returning to Iraq to find a job.

I also wanted to get a taste of what it’s like living in the U.S. to see if it matched my hopes and dreams.

Leaving Iraq: The Opportunity and the Reality

Before I could go back and reflect on my journey, I quickly had to adjust to staying in the U.S. long-term because 2007 was not a good year for Iraq, so my family had left.

I ended up pursuing asylum for political and religious persecution.

That Was the Beginning of a New Kind of War

Only this one was fought with paperwork, legal proceedings, endless bureaucratic expenditure, and the unpredictable waiting game of the U.S. immigration process.

It took five years to be approved. Then five more years to stay in the U.S. to become a legal resident.

The only thing that kept me going was the belief that there weren’t militias running around trying to kill me.

I could still die any day from a car accident, natural death, or running into the wrong crowd. Being deported was also something that could happen and would lead to an immediate death, most likely by execution.

However, there was this supposed promise that as long as I followed the letter of the law, I should technically be okay.

Thirteen years. That’s how long it took to trade fear for freedom.

Freedom Came at a Price

There were so many uncertainties along the way, and it was such an expensive journey that I’m still not where I should be financially compared to peers of my age who grew up here.

When you’re an Iraqi immigrant in the United States, especially one with a name like Mehmet, which I legally changed from Mohamed, and a degree from a non-Western university, the American dream isn’t handed to you. My credentials didn’t matter.

I was told I was overqualified for fast-food jobs and underqualified for the jobs I wanted. Health insurance? Only if you were full-time, and even then, good luck. Want to go back to school? Hope you like student loans.

I wasn’t angry—I was disillusioned.

It Is Hard to Describe the Dichotomy of Being Caught Between Cultures

Back in Iraq, I’d been taught that America was the land of opportunity. But once here, I saw that the opportunity came with fine print.

This was supposed to be the Land of the Free and the Home of the Brave.

I tried to pursue the American Dream of Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness. However, now that I wasn’t just experiencing America through the lens of its pop culture media, I realized it’s all fiction.

It’s simply a utopia that Americans aspire to reach, but that carrot has been keeping the engine going for those higher-ups who do experience the so-called American Dream.

You needed connections, citizenship, and luck. You needed to know how to game a system built for people who’d been here all along. And if you failed, you were told, “Well, why don’t you just leave?”

But that wasn’t an option. My family had already fled. My life was here now, in the same country that had raised me on cartoons and then made me feel like a stranger at the checkout line.

Like Many Iraqi Refugees and Iraqi Americans, I Learned to Adapt

I learned to blend in, just like I did under a dictatorship. I found friends.

Then, I learned which spaces were safe and which weren’t. I stopped arguing about politics in public and made peace with the fact that I might always feel a little caught between two worlds.

The truth is, I didn’t come here to chase the American Dream.

I came because I wanted to survive. What I found was a complicated country—flawed and fascinating. It’s a place where people still believe in resilience, even if they forget what it actually takes.

Sometimes, I think back to those cartoons. Looney Tunes was chaotic, yes—but it was also honest in a way most grown-up stories aren’t.

Wile E. Coyote never caught the Road Runner. But he never stopped trying, either.

More Than My Immigrant Experience: Resilience is Ingrained in Who I Am

There’s a quote from Looney Tunes that I think about a lot:

“I knew I shoulda taken that left turn at Albuquerque.”

It’s a throwaway line. A gag. But it resonates.

For years, I wondered the same thing: should I have stayed in Iraq? Should I have turned left instead of right during my immigrant experience? Was Billings the destination or just a detour?

Now, I realize that every turn was the right one because it got me here. Maybe not at the top of some fictional American dream, but in a place where I can tell my story.

I may not be a cartoon character, but I’ve survived falling anvils, too.

And I keep getting up.

And maybe, just maybe, there’s something beautiful about chasing freedom with a cartoon rabbit as your guide.

“That’s all, folks.”

— Mehmet Casey

0 Comments