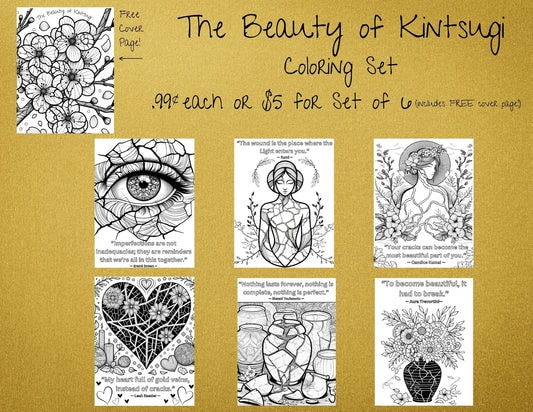

When something fractures, what do you do? Do you toss the broken pieces or do you repair them? The Japanese art of repairing broken pottery with gold is known as kintsugi.

Gold lacquer repair techniques highlight the broken places and turn ordinary broken objects into works of art.

In our consumerist culture, we frequently grow frustrated with broken things and toss them. This attitude can extend to damaged parts of ourselves and others.

Instead of casting aside the pieces, we can create beauty by highlighting the cracks. The damaged pieces can become gorgeous art riddled with gold seams.

But what happens when it’s not something physical that has been crushed, but a life trajectory?

The Day My World Broke

It started off as an ordinary day. I dressed quickly for school, putting on a soft shirt, acid-washed jeans, two pairs of colorful slouch socks, and moccasins. I carefully stirred food coloring into my oatmeal; pink oatmeal tasted better.

The sky was cloudy, and the slight wind rustled the changing leaves. It was a crisp fall morning as my brother and I skipped to school.

Nothing indicated that before the morning was over, my beloved teacher would break me.

I stood in the rubble, trying to hold on to the scattered pieces of myself as some disintegrated beyond repair. I was a little girl and didn’t know what to do. But I was desperate to hide the damage.

Although I loved broken, neglected things, I viewed my destruction as an indication of my worthlessness.

I built a wall around my heart to hide particularly valuable pieces of myself, protecting them from further breakage.

That also limited my healing for decades.

Introduction to the Japanese Art of Kintsugi

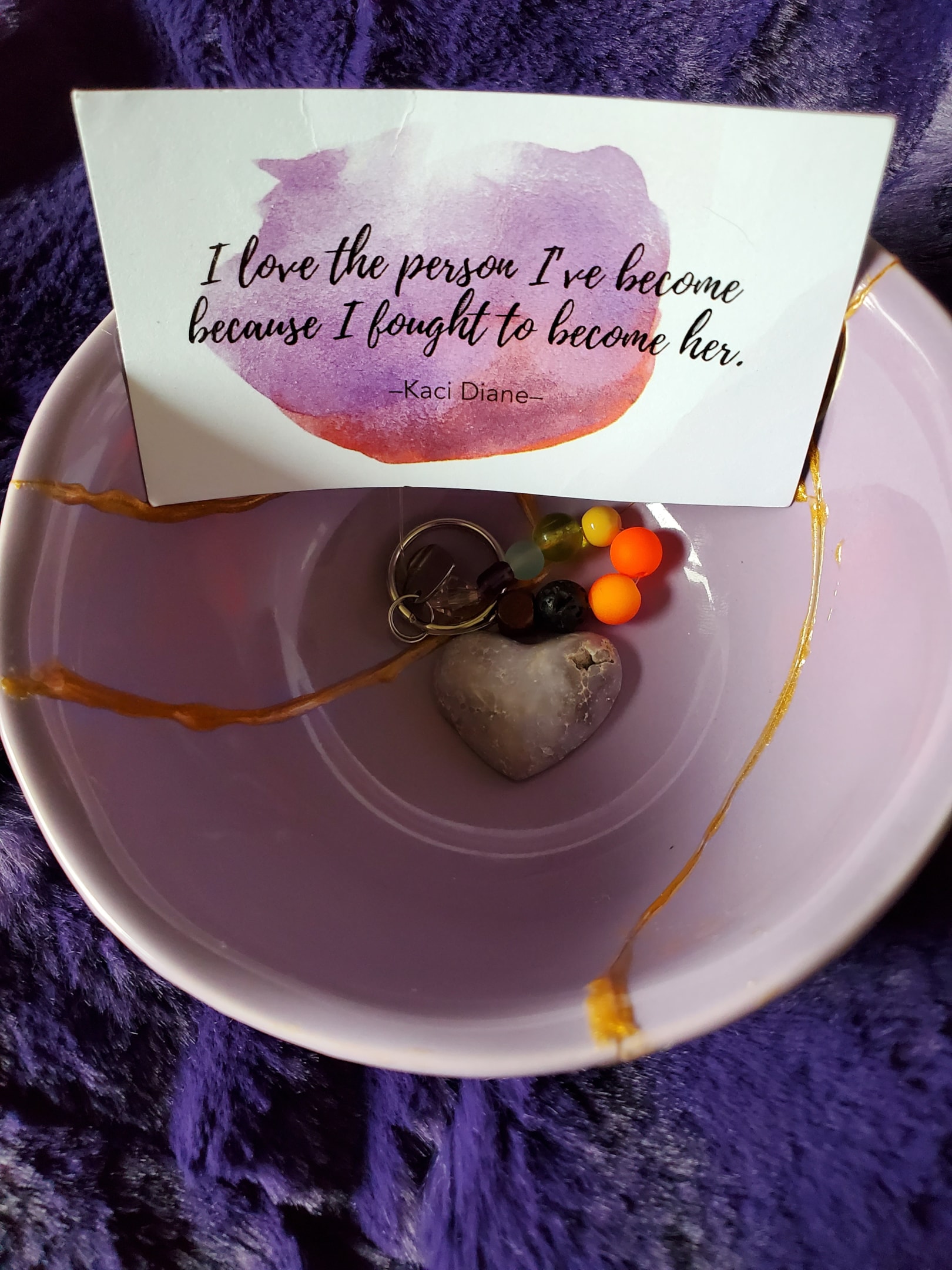

In May 2023, I attended a four-day retreat for survivors. A few hours into our first day, my group went to the art room for our first activity, kintsugi.

This activity was designed to teach us many lessons, including the Japanese philosophy of embracing imperfections and flaws and highlighting resilience.

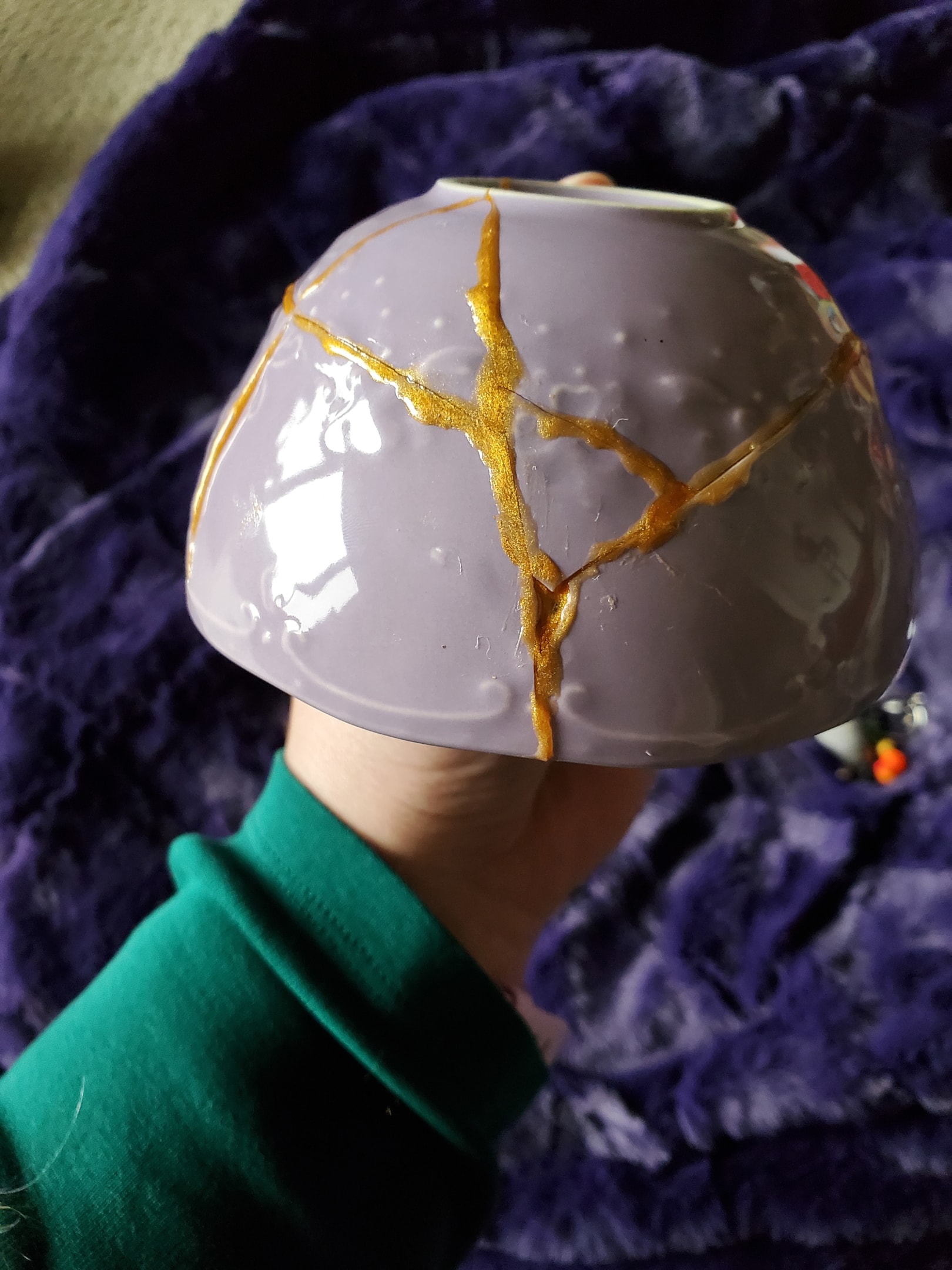

I chose a bowl that spoke to me. It was purple—my favorite color—and had butterflies decorating it. Butterflies are a symbol of my healing journey.

While it was pretty, it looked like an ordinary dish. I didn’t know where it was created, how it had come to be, or what had happened to it.

Now, I had not considered deliberately smashing valuable pottery—or any dishes—to create contemporary art. I didn’t know kintsugi or other ceramic repair techniques.

I felt uneasy about purposely shattering something, even though it needed to break to be mended with the kintsugi technique.

Embracing Wabi-Sabi and the Idea of Impermanence Through Kintsugi

I covered the ceramic ware with a towel. Then, I took a deep breath and brought the hammer down.

I forever changed its story, trajectory, and purpose, just like my teacher had done to me.

I handed the hammer to the next person and cautiously lifted the towel. The pottery was in pieces.

I thought with compassionate sensitivity about the little girl I had been when my teacher shattered me. Since I had long feared the extent of the harm, I hadn’t been fully existing.

My culture indoctrinated me with the idea that aesthetics mattered more than reality. It implied that pretending to be whole had more value than attempting to repair any damage.

I took that idea to heart, as I was desperate for love. I didn’t know that I could use metaphorical gold to create art out of the devastation.

In Japanese culture, there is a term that describes this process: wabi-sabi. Wabi translates to “less is more,” and sabi means attentive melancholy.

Andrew Juniper says “Wabi-sabi refers to an awareness of the transient nature of earthly things and a corresponding pleasure in the things that bear the mark of this impermanence.”

This concept ties in nicely with the Japanese art of kintsugi.

Kintsugi: The Art of Golden Repair

I tenderly sorted the shards of the bowl. Some pieces were dust. The vessel would never look the same. Nor did I.

We were given popsicle sticks to use to apply the epoxy mixed with fake gold dust. Immediately, my perfectionist self started fretting about the inability to neatly glue the pieces together.

I breathed deeply and let go of any hopes of a perfect project. I reminded myself that humans are messy, complicated beings, including me.

If my project turned out differently than I’d hoped, I would still be ok. There is beauty in imperfection, even in my own.

Then they told us to hold each piece for five minutes. Five minutes?!? How could I get all the pieces together before our time in the art room was up?

My anxiety crept up, and I wanted to rush things. I forced myself to slow down.

But when our time was half up, I gave up on taking the time to hold the pieces together. I became fixated on finishing.

Of course, those shards fell apart. By rushing, I’d lost time and made more of a mess, with strings and lines of glue now stuck in odd places.

My eyes teared up as my frustration grew, and my inner critic became loud. Yet in that moment, a realization occurred.

Rebuilding this bowl was a metaphor for my healing journey. This entire process mimicked healing.

Applying Kintsugi to My Healing Journey: The Art of Self-Repair

In my healing journey, I excavated hidden pieces of myself.

I sorted through the fragments, just as I did with my trauma and myself. Then, I carefully fit pieces together, like a kintsugi master might.

I glued the pieces together in a way that would highlight the beauty within and make them stronger. Just like I did with myself.

Therapy, writing, speaking, art, yoga, meditation, and more made up the glue in my journey. The love and support of my community represented the gold.

I’d tried to rush myself because of outside pressures. Our society treats breakage as something to rapidly fix.

Well-intentioned people told me I didn’t make progress quickly enough. They wanted me to immediately heal, despite the extensive harm. But by rushing, I fell apart again, messier than before.

I needed to take my time and forgo perfection, celebrating progress instead. I moved one step at time, forward, backward, sideways, and even forging a new path entirely.

My technique changes based on what is needed. I don’t follow one theory or method; instead, I meticulously craft what works best for me.

I attentively glued one piece to another and waited for it to set. It’s about being slow and deliberate, careful and considerate, and letting things take time to settle. Patience is essential.

Taking My Time and Practicing Non-Attachment to the Outcome

As I paced myself and ignored the outside limits, the dish came together. Not perfectly.

The initial breaking caused lasting scars. Some pieces are slightly crooked as well. My kintsugi technique needs more practice, and I need more patience.

It still needed to cure and fully set, and carelessness would cause it to fall apart.

I carried my bowl over to the counter so it could set it down, and I let go of worrying about the outcome.

I let go of the need for perfection and control over the bowl’s journey. I let it be and unwound, embracing wabi-sabi as well as kintsugi.

On the last day of the retreat, they gave us our bowls. What had been a fragile mess—much like me before commencing this journey—now held strength. It was a new object lined with gold that literally illuminated the broken pieces.

It was a physical expression of my breaking and healing journey, as well as new art.

This bowl has more beauty and wisdom within and because of the scars. It has a story to tell and lessons to teach.

As I reverently held my bowl, marveling at the imperfections that gave it grace and beauty, I noticed that one of the missing pieces formed a heart shape in the empty space.

I laughed in delight, as hearts have been an important symbol for me throughout my life. I center love in my worldview.

A Work of Heart From Japanese Art

Although some may look at the bowl and see something that is broken and useless now, I look at it and see a work of art. I see a journey, a message, a story, and hope.

I too am on a journey and have stories. My scars are part of who I am, and my beauty shines through the brokenness.

My healing knits me together with gold, stronger and glowing with love and light. As I speak my truth and share my journey, my life becomes more infused with joy, courage, and love.

I am a work of heart, and the traumas I’ve endured have made me who I am.

The bowl sits where I see it every day as a reminder of my dance along this healing path and the lessons I learned during the kintsugi process.

Have you tried kintsugi before? Let us know your experience with the ancient Japanese art form in the comment section.

0 Comments