Trigger warning: This story references sexual abuse as a child.

I was unaware of the concept of books as windows, mirrors, and sliding glass doors until I was in my Master of Education program. Understanding the idea that we need to see ourselves represented in literature helped me view my childhood and young adult life in a new light.

When I was a junior in college, I finally read a book that reflected one of my main identities. Until that moment, I thought of myself as defective.

Since I did not fit the stereotypes that represented all I had heard or read about being a lesbian, I felt as though I belonged nowhere. I re-read Annie on My Mind (*affiliate link) as soon as I finished it.

Still unable to accept that I found representation in the pages of a book. This meant I was not alone, after all.

I no longer had to pretend to be someone else all the time. I could label myself and learn about the history, uniqueness, and complexity contained within my community. Others like me existed. I belonged. I had a place in this world and no longer needed to pray for oblivion.

This book altered the course of my life. It helped me see myself and learn that I have inherent worth.

What do the terms mirrors, windows, and sliding glass doors mean?

Dr. Rudine Sims Bishop developed the concept of books as mirrors, windows, and sliding glass doors. A book acts like a mirror when the reader sees the reflection of their identities and experiences of their own lives on the pages.

Majoritized groups see themselves represented constantly. However, minoritized groups may not see themselves represented outside of stereotypes—or even represented at all.

A book can also function as a window through which the reader can see the world through the experiences of someone different from themselves. Sliding glass doors are a portal you open and walk through.

When literature transforms human experience from something you read about to something you empathize with, it has moved you through the glass doors.

Readers Need Diverse Books of Different Lived Experiences

Literature is powerful, especially when it represents those traditionally excluded from curricula and other media. This narrative erasure impacts all people, sending an implicit message about whom the culture deems valuable, worthy, and even human.

Children need to see aspects of themselves and their lives authentically represented in children’s books. When young people can recognize through representation in texts that others have similar experiences and/or aspects of themselves, it:

increases self-confidence and self-affirmation

aids in identity development

fosters validation and belonging

improves reading comprehension and motivation

provides models for working through challenging life experiences

Besides seeing oneself reflected in literature, readers need to encounter representations of those who differ from self. This will help all our children benefit from the powerful lesson of diversity.

Books that function as windows (seeing into the lives of others) and sliding glass doors (engaging with the text and emerging changed) can help with:

building empathy

decreasing prejudice

fostering understanding

encouraging new perspectives and interests

promoting creativity

We Are Not One Dimensional, and Stories Should Reflect That

Since all of us have multiple identities and various experiences, the same book can function as a mirror, window, and sliding glass door. A heterosexual woman might read a book like Annie on My Mind and find herself not identifying with the sexual orientation of the main characters.

However, she might have had an experience where she realized that being true to herself was more important than meeting someone else’s standards.

Readers need access to myriad representations of different identities. They notice when they feature characters that have few or no representations, which can send a devaluing message. As Dr. Sayantani DasGupta stated, “Narrative erasure is a kind of psychic violence.”

By itself, this lack of representation can have devastating consequences. However, when combined with negative messages from society, such as institutional and individual racism, heterosexism, cissexism, and additional biases, it can cause considerable damage.

Another harm of having certain experiences rendered invisible is that it can lead to someone not recognizing what occurred to them or thinking that no one else experienced something similar or had an identity like theirs. I know well the consequences of narrative erasure.

The Trouble With Covered Mirrors, Boarded Windows, and Locked Sliding Glass Doors…

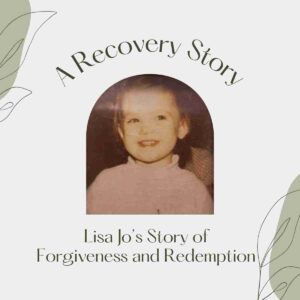

As a young child, I learned about “good touch, bad touch,” private parts, and sexual abuse.

I only saw child molesters depicted as creepy men. Therefore, I thought that only creepy men could sexually abuse children. The few news stories I heard reinforced this single story of who could molest a child and what counted as sexual abuse.

This was over three decades ago when less was known about sexual abuse, predators, victims, and the impacts of molestation. People rarely discussed sexual abuse, and literature and other media had few representations of survivors or predators. Even though I read voraciously, I did not encounter any books that mentioned molestation.

Consequently, when another little girl threatened me into letting her touch me, I did not know it was sexual abuse and kept quiet about it. Recently, I encountered a story that mirrored that experience, and I realized that the other child had molested me.

When my upper elementary teacher started grooming me on the first day of school, I told my parents that Mrs. Smith was too pushy. I had no other words to describe what happened that day when she kept stomping on my body boundaries. I had no concept of a woman pedophile.

Thus, I ignored my instincts, thinking I overreacted. Society taught me to trust teachers, parents, and females. I thought I was safe with others who had the same private parts as I, despite what had happened with that other girl.

Women were the most trustworthy in all the books I had read and the few TV shows and movies I had seen. I had faith in this single story with which society indoctrinated me.

Is That They Keep People Isolated and Unaware

Later that week, Mrs. Smith flipped up my skirt. When I turned around, face flaming, I expected to see one of the boys who routinely bullied me.

Certain boys attempted to look up my skirt, pull down my pants, etc. When I tried to tell adults at school, they punished me for tattling, so I gave up telling anyone and just dealt with it.

Instead of one of the usual boys, I saw Mrs. Smith. She smiled and told me she was helping me get lint off my skirt. I was confused but accepted her claim. She did not fit the stories I heard or experiences I’d had of the type of people who flip up skirts.

Additionally, she teased me about being embarrassed that a female saw my panties, causing me to second-guess my feelings and thoughts about the incident.

I trusted her more than I should have because of the single stories about women, teachers, and moms in books and other media.

When she told me that afternoon that she had seen some elastic loose on my panties, I thought that she was only trying to prevent me from the humiliation of having my underwear fall down.

When she “checked” and ran her fingers where she should not, I bought into her excuse that she only tried to help save me from embarrassment.

Narrative erasure led to me not understanding what was happening and not having the words to describe what she did. If only men could molest children like I had been taught, what could I call a woman touching my private part?

If I could not put words to it, how could I tell anyone who could help me?

Every Voice Should Count, and Each Story Matters to Someone

When she started stripping me to molest me, I felt lost. I could not even tell myself about the experience because I had no language for it. I made myself forget.

When she did it again, I tried to run—my body remembered what my brain did not. Then it happened again. And again. And again.

I kept silent. The sexual abuse worsened. My voice could not even form the words to tell, and I kept throwing them away as soon as they appeared in my mind. It was impossible that a woman was molesting me because all the stories taught me that did not happen. Ever.

I stumbled through that school year in survival mode. The following year, when it occurred to me she might harm another little girl, I went to the school counselor and tremulously spoke up.

After I told, it went mostly as Mrs. Smith had threatened: the police did not believe me because it challenged the narrative they knew.

I searched desperately for other stories like mine and found none. Because of a lack of mirrors for my experience, I suffered mostly in silence. I opened up a few times as a young adult.

Some people supported me, while others unintentionally made cruel comments and “jokes” about a woman molesting me. They had never encountered a story like mine and lacked the perspective and empathy that comes from reading similar stories.

The lack of literature serving as a mirror for me caused a great deal of harm, including negatively impacting my self-esteem and prematurely halting my healing journey for decades.

However, it also made me passionate about providing books that would reflect my students’ experiences and show them a window into other people’s worlds.

I quickly realized that published literature vastly overrepresented majoritized groups. I could not locate books that mirrored some of my students’ identities and backgrounds.

There are Still Not Enough Books and Resources For Children to Read

While more inclusive books and children’s literature are being published now than even a decade ago, recently, there has been an organized pushback against inclusion. Book challenges and bans are steadily rising.

School boards, administrators, teachers, and librarians are removing diverse books from classrooms and school libraries, ensuring once again that only some students have access to representation and are validated, welcome, and safe in those schools.

The books being challenged and removed are mostly by or about LGBTQ+ and/or BIPOC people. This sends a negative message about these identities and increases prejudice and bullying, which can lead to higher risks of suicidal ideation or actions.

Children need access to books that serve as mirrors, windows, and sliding glass doors

We live in a vast world full of people with a multitude of identities and experiences. The suppression of certain narratives harms everyone, especially the minoritized groups targeted.

Single stories make it easier for people to dehumanize and oppress others, as well as cause people to suffer in silence, not knowing words for their experiences or that others have faced something similar.

You did a great job putting words to what can’t be said. Thank you.

Fabulous